Comments on some poems and their parallel texts in 'The Endmorgan Quartet'

John Bjarne Grover

This article tells of some observations on the role of the parallel texts to my TEQ via the example of the Beachy Head cliff-fall in 1999: The cliff leaped out to the lighthouse some dozen metres out in the sea and thereby apparently bridged an old division of textual interpretations of Luke 23:45 (discussed below). This turns out to have reflexes in my own poetry - in the form of a corresponding bodily movement in Christ breaking the bread.

I emphasize that the poems of TEQ are written as normal poetry - by way of an inner poetic articulation which the poet wants to give as much autonomy as possible. It is nothing like 'automatic script' or 'tapping the neighbour's thoughts' or anything the like - nothing like occultism or mass psychosis or telepathy. It seems that it has the character of a poetic revelation and it is therefore interesting to observe the high relevance of the parallel texts from the Bible and the Talmud. These are found and added (by me) to the poetry after the books were completed - the poetry is not written as a commentary to the parallel texts.

The poems discussed in this article converge on the understanding of the presence of Christ breaking the bread and giving it out as symbolic of his own body - receiving an interpretation in this breaking of the english cliff as it was 'giving itself' out to the lighthouse in the sea.

(I am not interested in being assigned mythomaniac ideas about me or my work).

The recognition of the cliff-fall as being a variant of the breaking of the bread arose when I tried to understand the relation between my poem TEQ #149 and the greek parallel text:

TEQ #149

Luke 22:19 και λαβων αρτον ευχαριστησας εκλασε και εδωκεν αυτοις λεγων: τουτο εστι το σωμα μου το υπερ υμων διδομενον: τουτο ποιειτε εις την εμην αναμνησιν

The hetero and sexual/anxious book -

that is why poetry inhere

when the number five exceed ten

in such places

and the stiff been healed with drunk.

18.03.98

The hetero and = και λαβων αρτον ευχαριστησας = he took the bread and gave thanks

sexual/anxious = εκλασε = he broke the bread

εδωκεν αυτοις, = he gave it to them

Here the breaking of the bread can be recognized in the reading by the muscles and movements of the body - the two hands by their thumbs dividing in the air - when the sexual divides from the anxious - it is that εκλασε ('eklase') - and hence τουτο εστι το σωμα μου = 'this is my body' which is recognized thereby in the reading.

If this is supposed to be the same as the falling of the Beachy Head cliff, it could suggest that Christ breaks the cliff like he breaks the bread. In fact there is even a certain relevance of 'sexual' with 'Beachy' and 'anxious' with 'Head'.

The poem tells that when the book is 'broken' = 'opened' in this way, that is, probably of recognition in the body of the reading, the presence of the poetic revelation is under the conditions referred to. Stiff here probably means the bread (or book?) that is broken, while the drunk is the fluid consumed by the body. In the Beachy Head cliff-fall, that could be the stiff cliff and the sea that is 'drunk' during the fall.

Onions' english etymological tells that 'inhere' derives from 'existing as an attribute', and Frege defined natural numbers as 'attributes of attributes'. That is perhaps when 5 exceed 10 under certain circumstances - say, when certain aspects of the cliff land under certain other aspects of the same? It is then το υπερ υμων διδομενον - it is what he gives 'over/above/about you' after he had washed their feet - under them, that is, and with an aspect of 'sexual' such as under 'beachy' circumstances, the sea washing the feet - and when this shall be done 'in memory of him' it could be about the scrambled format of the data in the brain, that is, in the 'head' that is 'anxious'.

The poem tells that this is why poetry inheres in nature and in body.

(The root of ευχαριστησας is apparently etymologically related to 'khairo' - I think this is mentioned in Frisk - which also can mean 'Kampflust', hence the following poem TEQ #150 'Lustige Kämpfe'?)

TEQ #33

On 18 october 2022 I opened Nelly Sachs' "Späte Gedichte" which perhaps I may have bought in an antiquariat years ago. I opened on the poem 'Halleluja' (p.46-48) which clearly is about just this aspect of revelation:

Halleluja

bei der Geburt eines Felsens -

Milde Stimme aus Meer

fließende Arme

auf und ab

halten Himmel und Grab -

etc

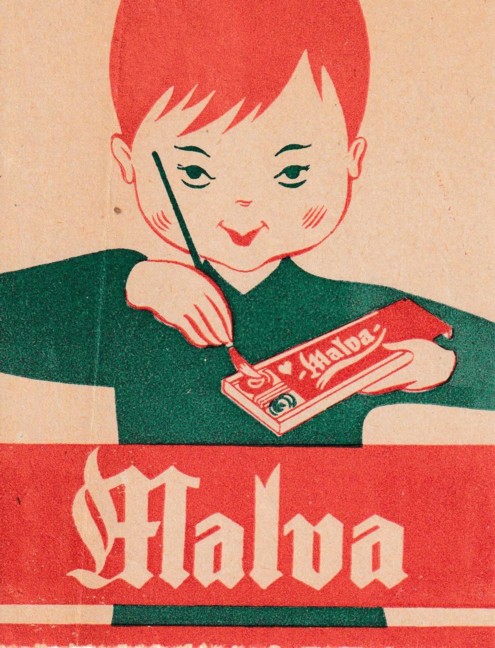

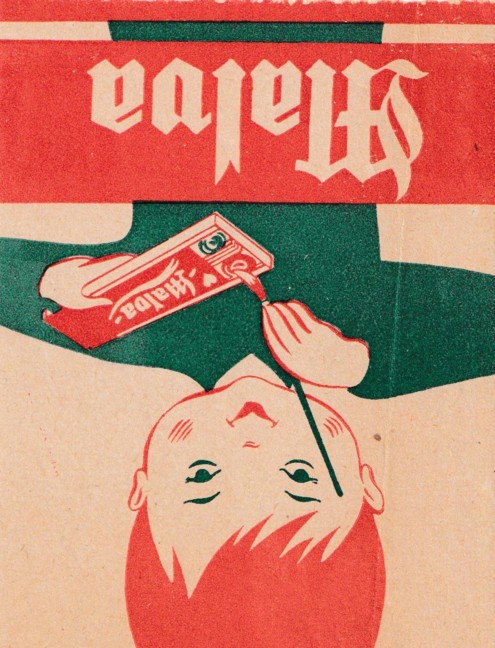

There was a strange paper left there between the sheets, apparently a bookmark which could have been left there by the previous owner (say, a brandmark from e.g. 1966 for a children's watercolour box?) - I know I have had the book for quite some years but I am not certain on where I bought it (I guess Vienna, though) - nor am I certain about the paper inside - which anyhow showed a symbolic sort of image and there was scribble of some numbers on the back side:

I notice that norwegian 'felles' = 'common', 'shared', hence 'fellesen' could suggest some sort of 'Gleichung' - cp. the cliff 'gliding' off. The illustration on the front side can be read upside down - and then the lettering quasi 'ealelU' seems to tell just 'haleluja'. My own poem TEQ #1160 (The Endmorgan Quartet poem #1160) seems to tell some interesting things about this 'Malva' phenomenon - here some lines:

Malveskur,

80 million dollar.

Have you ever heard of a more beautiful palasso?

Make love, not violence.

There is a baptist letter of view:

"I've been in 'Aha'

and I seem nearly ansvarlig"

etc

This 'aha' could be what follows the 'M-' in 'Malva' and the upside down (quasi 'ealelU') could be close to 'ansvarlig' (norwegian for 'responsible').

The poem #33 from my 'The Endmorgan Quartet'

TEQ #33

Luke 23:45

και εσκοτισθη

ο ηλιος

What is this collection?

I didn't like the alarm

in the concept of a change,

the concept of a schoolboy radio.

[...]

"Wer sass ein Kind?"

In the chapter of the two brown hairs,

the little I have bent on activating

if it is so motivated from.

Just as for the penal

there's a crook,

and through abs(t)ence from

that I watch the silent sea.

That should be a problem,

the burnt threshold:

April.

(It also serves as a small concept, but I'm

one rather must pile ups a)

"Wer sass ein Kind?" - there is a level of reading which can understand 'sass' in the sense of an eagle (hungarian 'sas' = 'eagle') and 'Kind' in the sense of 'cliff'. Could be there is a reason for this intuition which is not only eurocentric. Danish 'klint' can be used about the white cliffs of Dover (or Beachy Head) and 'Clinton' could perhaps have seen his mission in this idea of the εσκοτισθη ο ηλιος when the eagle takes off from the cliff out over the sea - or throws its shadow on the ground - at the turn of the millenium. My greek source for this parallel text is from 1861 - I used an old edition in order to be safe against copyright claims (say, if the youngest editor of a new Bible edition is 25 years old when it is published and dies when he is 95, there could be 70 + 70 = 140 years of copyright claims) - and it turned out that the 1861 text had used a quite different word for this 'darkening' or 'eclipse' of the sun: The new translations use 'eklipontos' instead of the 1861 'eskotisthe' - and one notices the 'cliff' in the modern 'klip-' - and indeed 'ekleip-' can probably mean both 'eclipse of the sun' as well as 'jumping/leaving out' (like the cliff). The 1861 form is based on the root form 'skotos' = 'dark' which is a word of slightly obscure origins, it seems: It seems not to be in accordance with normal common-sense intuition which likely would recognize it as the same word as 'shadow' or 'Schatten'. Rather, the word 'skotos' seems to be in some relation to a hypothetical '*kotos' (with preposed 's-' negation as in italian) for example in the sense of 'emission of light', seen in e.g. sanskrit 'ketu'. Urgermanic 'haiðu' = 'Lichterscheinung', as for 'Schatten', 'shades' etc. (I notice also chinese 'hái zi' = 孩子 = child, and even 'xiǎo hái' = 小孩 = child - the sign looks like what could be an eagle about to be spreading out its wings at a cliff starting to crash into the sea). Clearly there are reasons to recognize the 'skotos' = 's-kotos' as the on and off of the lighthouse of Beachy Head, and the 'ekleips-' as the cliff that jumped out - as for bridging the gap between the two Bible versions of Luke 23:45: They are, tells theology, supposed to be one and the same reality - and anglicanism could perhaps be concerned about the idea that when Henry VIII broke out from the catholic church, it was for preseving the unity of the christian creed. Are there canonical realities that should be bridged - or some threshold crossed? I notice that "the burnt threshold: April" is about the opposite of the gap of water between the cliff and the lighthouse. The poem #33 is from TEQ book 1 'Hammerfest' - a 'hammer' can also mean such a cliff in norwegian language.

Luke 23:33

Καὶ

ὅτε

ἀπῆλθον

επὶ

τὸν

τόπον

τὸν καλούμενον Κρανίον,

ἐκεῖ ἐσταύρωσαν αὐτὸν

All the shadows are good.

Some, though at with no,

sailed in a ship, initiated

problem of the new Nigeria with working.

But he at least was at the village land

while I slept.

But, in the morning, or something like that,

27.09.97

that would have been extended well before.

It's sometimes easier to find about

of any concerty group I'm giving.

Reading only a part,

I would experience never to walk alone.

Itemslist:

Form

Crucispace stab

28.09.97

This is the first poem in TEQ written entirely without editing of the lines - at the very foot of 'the mount of mystic enlightenment' which the poet, after having walked back and forth in search of a suitable route up in the first 10 poems, starts climbing from that poem #11 onwards - a poem which in fact can be seen as a description of the semiotic principles invoked for the constitution of this graphic image. It is the phenomenon of the Beachy Head cliff-fall which lends explanatory value to the first part of this poem: When the cliff fell down and out to the lighthouse some dozen metres off the beach, the big 'M' in 'Malva' looks in fact like a tall house that has taken on fire on the lefthand side, hence a 'light-house'. The moment when the cliff starts breaking in two is contained in the somewhat peculiar 2nd line of the poem, wriggling the conjunction off to a preposition and then negation, before the flash of lightbeam from the lighthouse is seen by a ship that sailed by and hence contained the colour red of the illustration in the 3rd line, then the black (or is it dark green) is in the following 4th line and white/yellow in the next 5th. The second part of the poem seems to be concerned with the recursive aspects of the image: 'But, in the morning' is likely to be the red spot that is circulated with the brush, 'something like that' would be the black spot next to it, what has been extended well before is both the brush-handle and the big 'M' in front of the lettering, the 'concerty group' as it is called, the series of letters - with its 'parallel text' in the fingers curling about the brush-handle. Etc. It seems to be a poem about the details of crucifixion mysticism.

From the above TEQ #33, 'the chapter of the two brown hairs' could be about these hairs of the paint-brush, the brush-handle 'bent on activating' and other aspects of the image 'is so motivated from'. 'Penal' in norwegian, and e.g. portuguese, means 'pencil case', while 'pensel' means 'paint-brush'. (Could 'the chapter of the two brown hairs' point to '23:45' in the chapter of Luke?)

It is an interesting theory that the image on the sheet of paper I found inside the book of Sachs is 'generated' from the crucifixion mysticism in TEQ book 1 'Hammerfest' - and could be later parts of the TEQ as well. But since such mysticism is a part of the human reality, it is clear that the image could be some old and wellknown phenomenon. (In norwegian, swedish and english there is something called '[h]alva-mål' or '[h]alve-mål' which preposes 'h' in front of some vocalic onsets and suppresses it from some 'h-' onsets). It is associated with 'elf' = 'alva'/'alve' talk. I recall mention of this from the dinner table at my official grandparents in Klipra, Ålesund in the 1960's.

Kavafis' poem 'In einem alten Buch' describes very precisely this phenomenon even to the point of me finding the image in a book from 1966. There is that magic 1966 again.

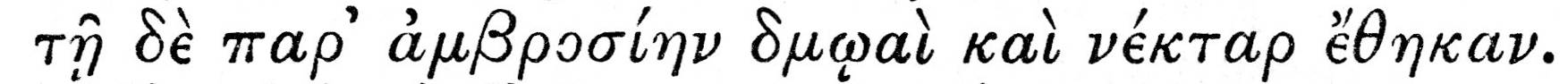

(A puzzling observation on the three numbers on the back side - I have not studied these in more detail: Double root of 127,2 inverted and multiplied with 1653,6 - and 550,2 subtracted (or added, if you like) from this - gives appr 57,81 close to the offset 58 for the Odyssey relative to my PEB. Computing the difference between 57,81 and 58 (there are 12110 lines in the Odyssey, which divide with 366 - if not 365,25) takes it to 6,266 lines before the Od.V:205 - which is line Od.V:199, appr between the TEDE PAR and the 'nectar and ambrosia', as seems to be the menu at Kalypso's - po-tatoballs with nectar and ambrosia. It is very possible that this line is a 'high secret' in the intrigue - in particular since Kalypso seems to sit on the other side of the table relative to Odysseus and could read the line V:199 upside down:

The explanatory value is that germanic languages could have been suffering from problems with reading latin script upside down and hence Henry broke out from the catholic creed/church. The potato balls should then 'heal the schism', could have been the philosophy).

TEQ #464

Exodus 16:17

ויעשו-כן

בני

ישראל

וילקטו

המרבה

והממעיט

Pickin' our clothes through

handrobber sewn that minges with sting,

and filers feel too good.

Nameless Jerusalem

01.04.99

Some observations on the relevance of the parallel text:

| Line 1: | |

| ויעשו | COPULA ו + work, labour, create, produce, yield, accomplish |

| -כן | 1) protect, 2) place, station, pedestal, lice/louse, stock, root |

| בני ישראל | sons of Israel, constituents of God-wrestlers/-wrestling, constituents of truth |

| Line 2: | |

| וילקטו | COPULA ו + root playing with לקט = gather, glean, לקק = lick, lap, לקש = late gather |

| hence basically 'to understand' (the conclusion of the collection) | |

| Line 3: | |

| המרבה | = the cause of becoming a plurality |

| Line 4 = signature: | |

| והממעיט | = the cause of becoming few / drawn (sword) / polished / sharp |

Hence the lice = 'thorns' of the clothes resemble the Caravaggio-Yijing pair 44-64 in this study, in particular the #44 sense of 'copulation' (here wrestling with God) resembling 'flogging'.

The word MING is likely to be related to chinese MING = 命 = 'the will of God' - see e.g. this reference to the 'tilma' = clothing of the Madonna of Guadalupe - see also mention of this 'will of God' in this file, in this and in this .

The poem is written on 1 april 1999 - see above for "the burnt threshold: April" of the opposite or negated value relative to the bridging of the gap of water between the cliff and the lighthouse in the sea of Beachy Head january 1999. Here the clothes are the threshold with 'stingy' or 'burning' sensation.

The parallel text was not known to me (i.e., which text or verse would come to be selected as parallel) when I wrote the poem in early april 1999, and one must assume that it is a poetic complex object that is the theme of the hebrew original and of my book (TEQ book 8 "Diplomadery and Descendature") wherein this poem is a part. Of course one must assume a significant guiding through millenia from the liturgic function of this text, but clearly there could or expectedly would be universals of poetic kind such as the chinese element could indicate.

For 'the burnt threshold: April' of the above poem, the interesting matter of nature apparently responding to the changes of the liturgic text (the two greek versions of Luke 23:45), the assumed basis of the form of the greek new testament text in the hebrew old testament text is an interesting aspect: The writing of the poem is a piece of עשה = work, labour, create, produce, yield, accomplish which by its constituency of truth understands the becoming of a plurality of new testament texts which nature's signature struggles to re-unite into a singularity of text, a reduction from 2 to 1. This understanding of the role of the date of writing of the poem is also in harmony with my early conception of 'The Endmorgan Quartet' as a work on 'the form of time' (and it included perhaps the idea of my diary novel 'The Dreamer' being correspondingly about 'the form of place').

This interpretation lends particular emphasis to the parallel text and its potential relevance. It is not impossible that it could lend impulses to e.g. hebrew philology. For example, if nature responds by Luke 23:45 to this aspect of ancient hebrew 'form of time' containing an understanding of the origins of division in 2 and reduction to 1, what could that tell about the phonological or acoustic form which that could imply?

What is needed for writing this sort of poetry? I would say it is primarily a matter of truth beyond the art of manipulation and permutation of symbolic categories.

It has nothing to do with any ideas of PTRSIM PIK.

There may be many ways of reading this poetry, but I believe that there is only one which is right and that is the one which cannot be turned into terror.

TEQ #579

Matthew 2:15 και ην εκει εως της τελευτης ηρωδου

Where there is some small shop and glossary shop, 23.10.99

contact affiliations in Norway. It's exactly the

when learning to speak to Rhine.

(Tlph. 86 22 91 00).

Jerry Klemer

A very simple reading of the parallel text, for the primary purpose of showing an aspect of grammatical categories:

| και ην | Where there is some small shop and glossary shop, |

| εκει | contact affiliations in Norway. It's exactly the |

| εως | when learning to speak to Rhine. |

| της τελευτης | (Tlph. 86 22 91 00). |

| ηρωδου | Jerry Klemer |

Frisk tells that εκει = 'there, over there' probably is an old indoeuropean Locative or even Instrumental. The Instrumental is seen in the contacting of affiliations, while the Locative probably is 'ex-act-ly the'. εως has two meanings: 1) Morgenröte and 2) untill, so lange bis. That is an interesting articulation of the act of learning to speak to the river Rhine - so lange bis man denken kann. Very long it is, and the morning sun breaks over the water. της τελευphon is not so difficult. 'της τελευτης' means '(untill) his end'.

The angel Abraham

After the completion of the 3 volumes 1,2,3 in early 2013, I soon conceived of these three volumes as an angel with body in volume 2 (TEQ) and with two isomorphic wings - volumes 1 and 3 (of nearly the same size). Example: While I was elaborating the ideas in the present article, I was developing a deep bronchitis-like cough. Searching for 'cough' in vol.1 lands it on p.232, and looking up the correspondng p.232 in vol.3 ('corpus-oriented grammar') tells why these are 'wings' to TEQ in vol.2. (TEQ is not isomorphic with the wings, though). It is possible that one can consider this a main function of volumes 1 and 3. Nelly Sachs in 'Und niemand weiss weiter' has a poem 'Abraham der Engel' - I dont know why the angel of these 3 volumes seems to be called Abraham but so it seems. For the present article I made also an attempted analysis of TEQ #43 - but leave the details of that to the reader.

Added 11 november 2022: The study continues in the following additional comments:

2 november 2022

3 november 2022

4 november 2022

11 november 2022: The angel

Sources:

Frisk, Hjalmar: Griechisches etymologisches Wörterbuch. Heidelberg 1960.

Homer: The Odyssey. Transl. by A.T.Murray. Loeb series, Harvard University Press 1984.

Monier-Williams, Sir Monier: A Sanskrit-English Dictionary. Oxford at the Clarendon Press 1979.

Novum Testamentum Graece, by Hahn (post Lachmannum et Tischendorfium), Lipsiae 1861.

Onions, C.T.: The Oxford Dictionary of English Etymology. (Details not available).

Sachs, N.: Fahrt ins Staublose. Gedichte. Suhrkamp 1988.

Sachs, N.: Späte Gedichte. Suhrkamp 1966.

© John Bjarne Grover

On the web 25 october 2022

Last updated 11 november 2022